This time of year, the losses in the area of music for Holy Week strikes me. I look through the Liber Usualis and I compare with what appears in the Missalette, and the result is absolutely devastating. Then I compare what is in the modern Graduale – which isn’t all that different from the old Graduale – and the effect is the same: a sense of near-total loss. Even our own schola, which strives to be liturgically proper and works hard to retain and revive, ends up singing truncated versions and perhaps 30% of the total music that is given in the books. As for the Missalettes, one wonders if the compilers ever even bothered to look at the normative liturgical books for the Roman Rite.

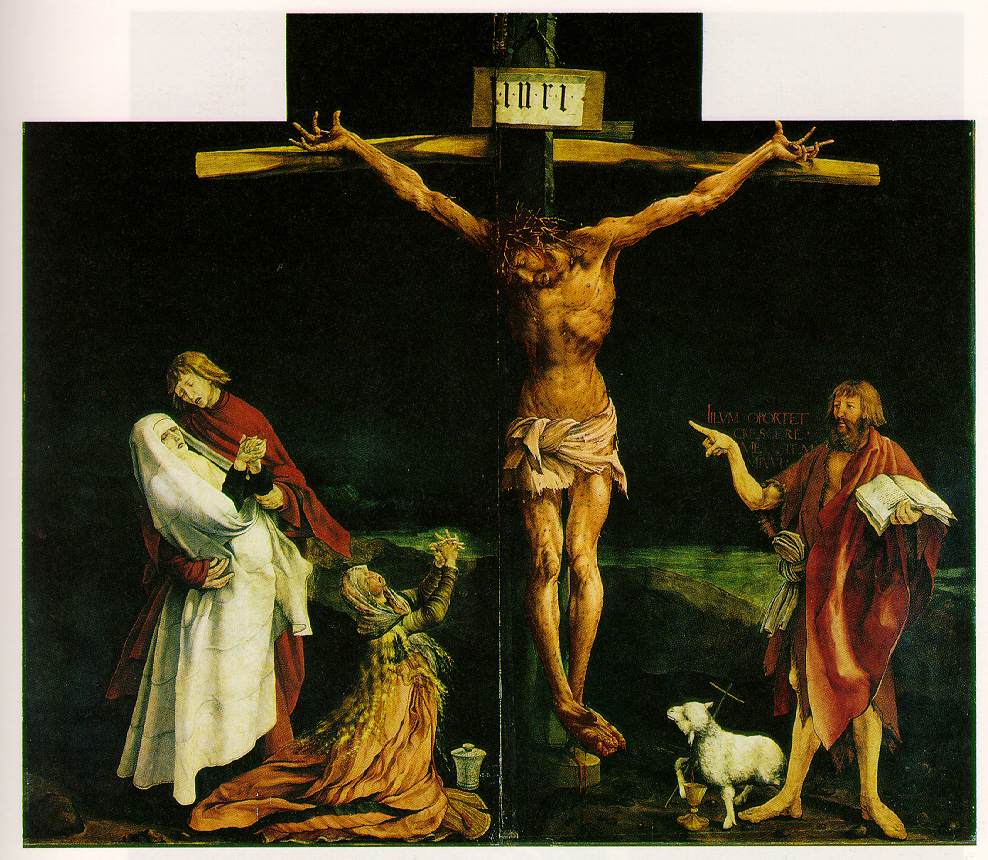

And yet what is given in the authentic liturgical books is absolutely unbelievable and stunning. The sound and feel of the chants are unlike anything else the entire year. The chant hymns are jewels. The narratives are set in unusual formulas that do not appear anywhere else. The drama is extremely intense. I would not call the music “beautiful” in the normal sense. It is instead severe, strict, stern, dark, emotional, alarming – choose whatever word you like. The overall effect is not what is called beauty in the sense we think of that term. No one walks away with the same sense of inspiration that you get from a concert or even from a regular liturgical motet. Instead, there is a sense of something else. Terror perhaps? Shock? I’m not sure what to call it.

And yet I suspect that this is not what will happen in 95% of parishes. Why have we lost so much? Even after years of study, the full truth eludes me here. I don’t really understand how this could have happened. Maybe our culture is afraid of everything Holy Week represents? Can we not handle the truth? Perhaps that is part of it.

In any case, there is so much work left undone in the area of sacred music. But the reclaiming of Holy Week – not just the music but the sensibility that the music represents – must be part of the agenda.

"Maybe our culture is afraid of everything Holy Week represents? Can we not handle the truth? Perhaps that is part of it."

Instead of trying to change the surrounding "culture" (or lack of it) according to the Word of God, the Church is becoming part of its God-alienating features. These missalettes have become just another form of the multibillion dollar "pop culture" industry, and simply feed the de-Christianising of American and Canadian societies: make the liturgy entertaining for the most common denominator of the faithful's "culture".

Many of the chant texts for Holy Week from those books you mention may have their origin in pre-Constantine society, where the zeal for the Lord usually lead to martyrdom, to follow Christ on the Cross that is being recalled that week. After Vatican II it did not help that the resurrection seems to have taken the limelight, even though you cannot have that without the Cross first. Even the Holy Thursday Mass of the Lord's supper is no longer associated with the sacrifice on the Cross except perhaps accidentally through the Introit, which few parishes sing in any case.

I would sure like to have a return to the "Imprimatur" from the local bishop for any printed texts used at the liturgy in the diocese, but somehow I do not see that happening because of the Bishop's fear of being "divisive', or perhaps too many would not find themselves competent for the task.

With few exceptions, the bishops would not be "competent for the task". So many are themselves clueless clods totally unappreciative of the Church's liturgical heritage. Added to that, they surround themselves with others similarly lacking in the knowledge and the talent.

Until there is a complete return to the sacred, a re-discovery of the richness of the Roman liturgical patrimony, and this is conveyed to the next generation of priests there is no sense wishing for the return of the Latin liturgy. When the people only look for the facile and pseudo folk diversions. They're idea of an "ancient liturgy" is something their grandparents might have experienced in the 1950s.

As for Holy Week, St. Clement's Anglican Catholic Church in Philadelphia will give you a better idea of what Holy Week once was like in the Latin Church than any modern Catholic Church could possibly do. Or, better yet, go to an Orthodox Holy Week where one never loses sight of the Cross throughout the Lenten season and the sacred triduum.

It was precisely this wholesale destruction of Holy Week, and in particular the complete elimination of Tenebrae and some of the most ancient chants and offices in the repertoire (the Lamentations for example) which musically and spiritually brought me to the traditional rite/ extraordinary form. While I would in no way label myself a "trad" and I tend not to identify much with those who do, when I was introduced to Tenebrae as a student, the destruction of Holy Week in the ordinary form was hard not to see.

I know I am not alone, and I know of communities who use the new Liturgy of the Hours through the year, but revert to the old Office for Holy Week, or as in the case of the Norbertines, to their traditional rite or usage. It seems that even those committed to the post conciliar liturgy feel there is something missing. (J. Morse)

The loss is simply and obviously diabolical.

I agree with Francis. Actually, most of what has befallen our now nearly destroyed patrimony is diabolical. Nevertheless, I try really hard to remind myself that the OF is valid and can be beautiful when it's celebrated according to the rubrics.

In my view, the destruction of Holy Week is due to liturgical entropy. Most parishes never celebrate an OF analogue to missa cantata. Most are content with the four hymn Gather hymnal sandwich "low Mass" Sunday in and out. Why should anyone expect that Holy Week will emerge in its splendor when the usual fare is so meagre? Most "music ministers" wouldn't know what the Improperia is, let alone spell the name. The OF Holy Week mess is a mash-up of ignorance, apathy, and the fear that someone out there in the pews will throw a fit if any part of the Holy Week schedule is changed.

My heart goes out to the traditional pastors who have to put up with pulp hymnal crap even during the triduum and Easter. Hang in there.

In my view, one of the greatest losses is in the Easter Vigil. True, much is still there,the lighting of the new fire, the lumen Christi, the Exsultet, the Old Testament lessons, the ringing of the bells and the playing of the organ at the Gloria. On the other hand, both form and content have been altered for the worse. In the old rite, the "vigil" part, including baptisms, that part taking place before the illumination of the whole church and turning to the festivity of Easter took about half of the time, and this paced what was otherwise a rather long service; it created a balance between the two clearly distinct parts. In the new rite, the Easter festivity is begun earlier, and does not sustain as well. The old music of the vigil, the threecanticles have been replaced by quite a few more tracts, many drawn from Lent. But this is not Lent any longer, and while the canticles make use of much of the same musical material, they are the lightest and most eboullient of this usage. They constitute a stage in the progress between the tracts of Lent and the music of Easter. Another loss is the lauds of Easter Sunday. This was a very brief form of Lauds, coming immediately after communion. This is where the now over-used three-fold alleluia really belongs. That lauds is one of the most ecstatic moments in all of the Divine Office; its brevity allows it to sustain that ecstatic quality, even though it comes at the end of a long liturgy. The Easter Vigil is the most unique Mass liturgy of the whole year; the new rite has worn down several points of that uniqueness—too much of the changes to it seem to be for the purpose of making it resemble a Mass on an ordinary Sunday.

Likewise, the Tenebrae is the most unique of all the Divine Offices of the year. It was already compromised in the reform of Pius XII by, perhaps righty, moving the liturgies on Holy Thursday and Good Friday later in the day. In my recollection, Tenebrae in the brightness of morning light did not quite make it. There is a slight recovery possible, however. The form of the Divine Office is freer than that of the Mass in this respect: those who do not have a canonical obligation to the Divine Office are free to use whatever form they elect. (This was true before the Council, when religious orders produced a number of "short Breviaries," abbreviation of the Divine Office for those engaged in active apostolic work, who could not manage to maintain the entire Roman office.) Thus it is quite acceptable to celebrate the Tenebrae in the old form; the crucial evening time is at least feasible for Holy thursday, since it is anticipated on Wednesday evening. My own choir does this on Wednesday, and it is an extremely moving liturgy.

Concerning the predominance of the secular culture, we must not forget that there is also a sacred and Christian culture. The early church jealously guarded its chant from secular influence, including that of instruments associated with pagan rites, and the tradition of unaccompanied singing still prevails in the orthodox churches and in the a cappella ideal represented by the Sistine Chapel and many other choirs. There have been times in the past when it was necessary to maintain that sacred culture quite indepentdently of the secular.

Concerning the beauty of Holy Week, Jeffrey is right to disassociate this beauty from conventional (secular) notions of beauty, which have become confused with such subjective notions as pretty, lovely, nice, etc. Rather the beauty of the liturgy and its music lies in the way it fulfills the scholastic definition of beauty–splendor formae–the showing forth and making more emphatic the inner nature of the liturgy itself. Gregorian melodies characterize and differentiate the liturgical actions which they accompany, and this is their principal beauty; the liturgy sung in Gregorian chant shows forth its nature incomparably more than the spoken liturgy can. Thus the beauty of Holy Week is that the music makes palpable the events of the Week, which on the surface are stark and not always pretty; but, in the context of the whole liturgy, which shows forth the birth, passion, death, and resurrection of Christ for us, this beauty bears a transcendent element scarcely shown by any other music.