Once again today, Mass was packed: every Mass, every pew without exception, from morning until night.

Catholics love Ash Wednesday. Priests often comment on how peculiar it is. It is not a holy day of obligation. Catholics could stay at home and luxuriate, stay at the office and work, avoid the traffic, avoid the fight for a parking place.

Instead they come. They come to receive ashes on their heads, and be marked as Catholics, a sign observed by everyone inside and outside the Church. And it isn’t exactly flattering to walk back into the office with a smudge on the forehaded. One walks around all day having to explain the meaning and where one has been.

Attending Mass on Ash Wednesday it isn’t a law in the world or in the Church. There is no penalty for failing to be there. And yet they come anyway.

Why?

It has something to do with the mark, the very physical evidence of the ceremony. The faith isn’t an abstraction in this case. It is instantiated in something we can see. It is not just an idea. It is a thing perceived by the senses. It is unlike anything we experience in the rest of the world: it is a mark of the sacred.

In some ways, in the sweep of history, this is an especially Catholic impulse, one that takes seriously the Incarnation as an empirical fact. That God would become man and take on human form in every way affirms as facet of our faith that the senses are not evil as the Manicheans would have it but rather a part of the created order that can made sacred through holy uses in holy spaces.

I’ve read various atheist tracts over the years that rail against every variety of religion and poke fun at the gods we are accused of inventing in order to quiet our insecurities. In these, Catholic Christianity is usually lumped in with all the others and dismissed as a sheer fantasy. But these writers are wrong in this sense: Catholicism is distinct for being a faith that is fundamental based on a series of physical facts perceived by the senses. Christ existed. He made certain claims for himself. These claims were heard. For these claims, he suffered and died.

If these facts are wrong, Catholicism is not true. But they are not wrong, and on these truths about what happened in time, in the physical world, form the foundation of our doctrine. The Incarnation is everything for us.

It is for the same reason that Catholics do not fear icons and images of saints, and we want our Churches to be beautiful and grand, not small and merely functional. The form is part of the faith. And so it is with ashes, which have this interesting intertemporal feature that is intrinsic to the liturgical year. The ashes are merely conjured up for use on this one day but rather come from the previous year’s liturgical experience of Palm Sunday, and thereby reach back and also foreshadow both Christ’s death and our own.

And so with ashes we cover three senses: the touching of our foreheads, the hearing of a reminder of our own mortality, and the seeing of the ashen cross on our foreheads. And here we have a case against the ideology that wants to purge Catholicism of its distinctive physical markings and the ceremony that makes them part of our lives. Catholics come even in the absence of a mandate in order to experience them. And we do so because we adore the perceivable marks of our faith. We adore the ritual. We adore those features of the faith that underscore features of the physical world that make our very lives sacramentals. Our faith is not just abstract. It is real.

A hugely important aspect of this, but one sadly neglected in our time, is our music. Catholic music is like the ashes on our forehead, a very old tradition with timeless meaning for lives. It is a physical sign of something much deeper. Ashes are visible evidence of the invisible. Catholic music is the audible sign of the inaudible. It is something we should hold on to, cling to in order to give the daily march of our lives a spiritual meaning.

What if one year the Catholic Church stopped giving ashes and instead proposed something completely new. You can use your imagination concerning what this would be. What would happen? Would people take to it very well? Not likely. It would end up killing a ritual, killing a tradition.

Something like this has happened to Catholic music. The sound of what was once something unique to our ritual was drowned out by something else entirely, and people thereby lost interest in it. Our children are not taught it. Our pastors do not insist on it. We don’t train people to sing it. We don’t expect excellence or standards. And we certainly won’t pay for it. The music lost its significance when it lost its connection to history and ritual.

I think this helps explain many of the problems modern Catholics have with the present state of Catholic music. It doesn’t transport us into a spiritual realm. It is something we perceive with the senses but it doesn’t connect us intertemporally, doesn’t draw us into something larger and more important than our own times and our own generation. It lacks that deeper connection to the whole ritual of our faith. It seems artificial and deracinated.

Let’s use the loss of the Marian antiphons as an example. They were once associated with a season. In Lent, we would stop singing Salve Regina and start singing Ave Regina Caelorum. Today, hardly anyone knows the latter song (even though it is very beautiful) and ever fewer know the former. These are songs of our faith, as much a part of our history as ashes on Ash Wednesday. And yet they were taken away or simply dropped for no apparent reason.

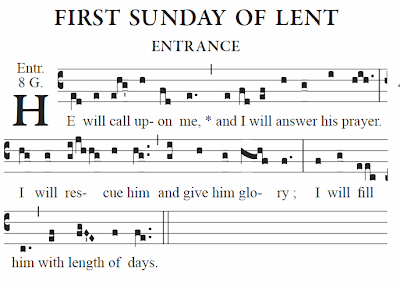

That is only the beginning. There are entrances, offertories, communion chants, sequences, Psalms and alleluias, and a thrilling set of ordinary chants for the people, each of them artistically brilliant, music that was born with the Roman Rite and grew and matured with it, bound up with its text and ritual through all of history. To neglect this body of music is no different from neglecting Ash Wednesday and its features. Like ashes, this music is not mandatory. But also like ashes, it can again become a critical feature of living life like a Catholic.

The musical treasures of the faith are not hidden away. They are there for us, more accessible than ever before in history. We only need to reach out and make them ours again, putting them to use in our lives. The music can be like the ashes: signs of an incarnational faith that doesn’t reject beauty and art or scorn the sense but rather embraces them all as signs of eternal truth. These features of our faith help us to believe what the world calls impossible and believe what the world calls unbelievable.

Sacred music belongs in Church. It is a specialization of the Church. The Church takes the raw material of notes and text and turns hearing them into occasions of grace. Just as no one thinks much of the ashes in the fireplace – there is nothing holy about them – so too do Catholics believe in their hearts that the music of the Church must be special and point to holy ideals. It can. And with the seemingly endless variety of chants in our history and music books of the Roman Rite, every single liturgical event can take on a special meaning in the same way that Ash Wednesday has.

We should rejoice at the traditions that have survived and enlivened the faith, drawing us to the liturgy even when we aren’t fulfilling an obligation. So it can be with every Sunday and every feast day – and even every day. We only need to reclaim those features of the faith that are timeless, holy, beautiful, and universal expressions of its core truths – with music as the preeminent example.