We tend to think of the papacy of Benedict XVI as the papacy that put the Catholic liturgy back together again, turning the “hermeneutic of rupture” into the “hermeneutic of continuity.” Rarely receiving the credit for preparing the way is John Paul II, who labored mightily and brilliantly during his pontificate—in a long and consistent series of liturgical teachings—to restore what had been lost and to prepare for a brilliant future. The July 5 announcement by Pope Francis of John Paul II’s pending canonization offers an opportunity for us to recall his extraordinary contribution to the restoration of sacred art, music, and liturgy.

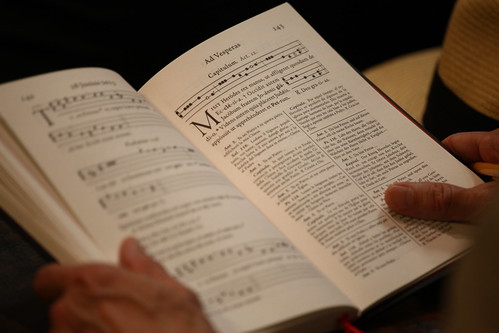

The legacies of John Paul II and his successor Benedict XVI are obvious from every liturgy we observe today at St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, and also many places around the world. Beauty is back. Chant is back. Even the traditional Latin Mass, the form used to open the Second Vatican Council but was later suppressed, is said in St. Peter’s daily, and is taught at seminaries around the world.

It turns out that the Age of Aquarius did not overthrow all things. Indeed, long-time observers of Vatican liturgy tell me it is more beautiful and more historically rooted today than it was in the decades prior to the Council. The message has been decisive and clear: The Catholic liturgy is ever old and ever new. The forms of the past remain valuable to us today, just as the developments of the future must necessarily be rooted in a deep love and respect for liturgical tradition.

These are lessons we know today but were evidently lost on that generation that took charge after the Council closed. They bequeathed to us a few harrowing decades. From one generation to the next, the liturgical forms became unrecognizable. Tearing up the pea patch was the prevailing sport. Everything new was admitted and encouraged while everything old was frowned upon or banned. It was a classic revolutionary situation, one with massive casualties and one never intended by the fathers of the Council.

The Council taught that Gregorian Chant should have first place at Mass but by the late 1960s, it had no place at all. Pope Paul VI was distraught and spoke with sadness: “we are in the process of becoming, as it were, profane intruders within the sanctuary of sacred letters… We do indeed have reason for regret, and to feel as it were, that we have lost our way.” And yet he pressed on, seeming to reflect in his own words this spirit of disorientation, rupture, and even revolution.

Karol Józef Wojtyła became Pope John Paul II eight years after the reformed Mass came into the world. The dust was far from settled. On the contrary, the earthquake that began immediately following the Council’s close was still rocking the Catholic world. The folk Mass—supposedly more “authentic” than music for the liturgy used for 1,000 years—had become the new normal. Old books, vestments, and statues filled the landfills. The old rubrics were wiped away. The priestly orders and convents were melting down. “Wreckovations” gutted great Churches and cathedrals. The only consensus was the absence of consensus.

In the course of John Paul II’s 28-year papacy, he undertook many initiatives to restore beauty to the liturgy, make it clear that not all art forms are admissible at liturgy, heighten respect for the past, and to take the first steps toward the restoration of older liturgical forms.

He took on directly what we might call the “cult of the ugly” that came to dominate Catholic culture since the mid and late 1960s. You could see it in the clothes, hear it in the music, and observe it in the architecture. The prevailing idea, rooted in a form of nihilism, was that high artistic sensibilities were necessarily elitist and inherently exploitative of genuine human emotion, which can only be expressed through spontaneous outbursts and improvisation. Choirs were gone, training put down, and excellence in general was disparaged and dismissed.

John Paul II, trained and experienced in the arts and holding a profound appreciation for the role of the arts in the expression of the faith, set out to inspire a new kind of idealism in the Catholic world, one that necessarily spoke to the liturgical and musical problems of the day. He took on the prevailing ethos and gradually but firmly got us back on course as a Catholic culture with a purpose and a dignified bearing.

“An examination of conscience so that the beauty of music and hymnody will return”

Hope you like my long piece at Crisis this morning.