Sacred Music Colloquium Registration Deadline

You are invited to experience the Sacred Music Colloquium, the largest and most in-depth teaching conference and retreat on sacred music in the world. Our 2013 program at the Cathedral of the Madeleine in Salt Lake City, Utah, offers new and expanded opportunities for learning, singing, listening, and interacting with the best minds and musicians in the Catholic world today! Avoid late fees and register before May 15, 2013.

Advent Calendar 2014

Just in case it helps with anyone’s long-range planning, here is the 2014 Advent Calendar of Hymn Tune Introits.

Square Notes for Beginners

I’m repeating the first course in reading Gregorian notation tomorrow (Sunday) at 5:00pm CDT. Join me!

Polyphony Kickstarter Campaign

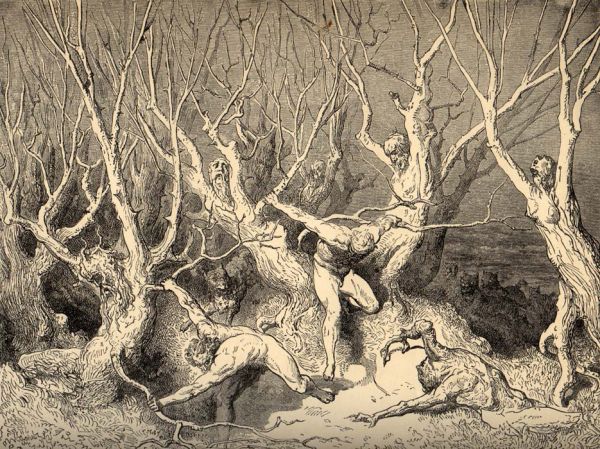

Dante’s and Boccaccio’s Contrasting Worldviews Expressed though Son

Hilary Cesare, a soprano in our choir, wrote this interesting reflection in school. Very interesting!

Dante’s and Boccaccio’s Contrasting Worldviews Expressed though Song

Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy and Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron are two monumental works of the late middle ages. The Purgatorio from the Divine Comedy explores the proper relationship between God and man and how this can be perverted by sin. The Decameron on the other hand is a work that explores the human relationships among people of varying class, gender, race or religion. The Divine Comedy is primarily concerned with divine things, while the Decameron is concerned with earthly, human matters. A strong theme is each of the works is that of song. The Purgatorio is filled with

examples of religious hymns and chants. In the Decameron, a song is sung at the end of each of the ten days. The song always deals with the topic of human love. There are also many examples of song in the stories themselves. The topic of song in the two works further illustrates the strong divide between divine themes in the Purgatorio and earthly themes in the Decameron.The first topic to be discussed is the way in which each work uses the parts of the Mass Ordinary to illustrate the narrative. Dante describes how the souls on the terrace of the wrathful sing the Agnus Dei in the midst of the black smoke:

I heard voices; and each one seemed to pray

For peace and for compassion on their sin

To the Lamb of God who taketh sins away.

Still Agnus Dei did their prayers begin:

One word was in them all, one tone rang clear,

So that the entire concord the seemed to win. (Canto XVI, 16-21)The souls repentantly chant the Agnus Dei as they reflect upon their sin. They direct their thoughts to the divine Lamb of God and their own importance diminishes. Another mention of a part of the Mass Ordinary is the Gloria. While on the terrace of the avaricious, Dante feels Mount Purgatory trembling and is afraid. However, Virgil

reassures him:Saying: “While I guide thee, be not thou afraid.”

Gloria in excelsis Deo they all cried,

By what from those nearby I understood

Whose words could through the shouting be descried.

Motionless stood we in suspended mood,

Like to the shepherds who first heard the chant,

Until the trembling ceased and naught ensued. (Canto XX, 135-141)The singing of the Gloria in the narrative signified that a soul had been purged and was ready to ascend to heaven. Dante beautifully compares the event to when the angels sang the Gloria to the shepherds in Luke 2:14. Dante’s purpose in writing the Divine Comedy was to direct the thoughts of the reader heavenward, and that is exactly what these two

descriptions cause.In contrast, Boccaccio’s mentions of the Mass Ordinary texts have far different overtones. In the ninth story of the eighth day, Boccaccio tells the story of an ignorant physician who wants to become friends with two painters in order to learn about their exciting lifestyle. He tries to become their friend by showing them lavish hospitality.

Because of this, one of the painters, Bruno, “painted a Lenten mural for him on the wall of his dining-room and an Agnus Dei at the entrance to his bedroom and a chamber-pot over his front door” (Decameron, 8.9, p. 620.) Although this is not an example of the Agnus Dei text used in a song, it would have suggested this idea to the medieval reader. Boccaccio places this idea that was employed so loftily in the Purgatorio, on the same level as a chamber-pot.

In another instance, he employs the texts of the Mass Ordinary in order to describe the scandalous behavior of a parish priest. The second story of the eighth day describes a priest’s attraction to a lady in the parish. “Whenever he caught sight of her in church on a Sunday morning, he would into a Kyrie and a Sanctus, trying very hard to sound like a master cantor when in fact he was braying like an ass, whereas if she was nowhere to be seen he would hardly open his lips” (Decameron, 8.2 p.556). Boccaccio does not try to uplift the mind to heaven by referencing the singing of these sacred texts, he is simply trying to colorfully and ironically describe the wretched behavior of his characters.

The text of psalm 50 is also mentioned is each work as being sung. In the Purgatorio, When Dante arrives in the valley of the late repentant sinners who died a violent death, he describes what he hears:

A people chanting, a little above our course,

The Miserere in alternation due.

When they perceived that I opposed perforce

My body to the passage of the ray,

They changed their chant to an “Oh” long and hoarse. (Canto V, 23-27)The Miserere, “have mercy on us…” is used here as it would have been used on earth. It is a supplication to God and a request for his mercy. However, when Boccaccio mentions the prayer, his character is not using it for a divine purpose. In the eighth story of the third day, an abbot convinces a parish wife to allow him to send her husband to “purgatory” so that the abbot could then have relations with the wife. The abbot drugs the husband and causes him to believe that he is in purgatory and whipped daily for months. When the woman becomes pregnant, she and

the abbot realize that the husband must come back from purgatory and be convinced that the child is his. The abbot drugs the husband again and allows him to wake up in his

tomb. When the other monks were surprised by this, “the Abbot pretended to marvel greatly over what had happened, and as soon as he was alone with his monks, he had

them all devoutly chanting the Miserere” (Decameron, 3.8, p.263). The purpose in this case is not to make a humble prayer to heaven, but simply for the corrupt abbot to cover

up his deceptive scheme. Once again, Boccaccio takes this sacred subject, but uses it to illustrate human depravity.The Purgatorio is filled with example of religious hymns being sung. A beatitude is sung on each terrace, as well as other hymns, such as the Te Lucis, (Canto VIII, 13), the Salve Regina (Canto VII, 82) and the Te Deum (Canto IX, 140). Directly before Beatrice appears in Catno XXX, several hymns are sung: Veni, sponsa, de Libano, alleluias, ad vocem tanti, senis, Benedictus qui venit, and Manibus O date lilia plenis. After she speaks to Dante, the end of the Te Deum is sung: In Te Domine, speravi.

Before crossing one of the rivers in the Garden of Eden, Dante hears the Asperges Me being sung (Canto XXXI, 98). This would have been sung at Mass during the sprinkling rite that calls to mind Baptism. The Purgatorio is filled with examples of sacred songs such as these. The songs serve to uplift and elevate man’s soul to divine things.

In the Decameron, each of the ten days ends with one of the ten youths singing a song. All ten of these songs deal with themes of earthly love. Some of them deal with the excitement of newfound and/or concealed love (Songs II and VIII), whereas others sing of unhappiness found due to love or marriage (Songs III and VI). The heavy emphasis of songs of earthly subjects illustrate even more the difference between Dante’s divine themes and Boccaccio’s earthly themes. There is only one example of an earthly love song in the Purgatorio. When Dante meets his friend Casella on the shore outside Purgatory, Casella begins singing one of Dante’s love poems set to music. Dante and those standing nearby were entranced by the singing. But then:

And lo! The old man whom all the rest revere

Crying, “What is this, ye laggard spirits faint?

What truancy, what loitering is here?

Haste to the Mount and from this slough be freed

Which lets not God unto your eyes appear.” (Canto II, 119-123)The earthly love songs in the Decameron are seen as a worthwhile pursuit of entertainment. In the Purgatorio, singing about earthly love is portrayed as a pointless distraction from divine things.

Dante and Boccaccio both use divine and earthly songs in order to more colorfully illustrate their stories. But the themes which they tend to invoke by these songs differ drastically between the two works. Dante repeatedly uses examples of songs in order to direct one’s mind to heaven. Boccaccio uses songs either to ironically illustrate

the depravity of his characters or to glorify earthly love. The ways in which songs are used by each author reflect the contrasting, greater purposes of the works.

Gregorian Chant as a Liberal Art

I heard the most fascinating lecture once, about the liberal art of Chinese calligraphy. The thesis of the talk concerned the training that young people received from the discipline of writing characters. Far from being simply a medium of communication, the process of learning to write characters was itself considered a liberal art: the kind of learning that makes people free.

Music is one of the classic seven liberal arts. It belongs to the intermediate stage of studies called the quadrivium, which followed upon basic studies, and prepared the way for philosophy. Music shows the proportions among numbers. It helps people to learn to weigh things, and to discern.

The need for these basic skills seems to come up again and again in the Church. People without thinking skills can easily be swayed. I remember talking to a colleague in an office, a faithful Catholic churchgoer and a capable employee, who was confused by a Dan Brown novel, The Da Vinci Code. She said, “How do we know it isn’t true?”

In the Last Gospel, read at the end of every Extraordinary Form Mass and read on Christmas Day in the Ordinary Form, we read, “In the beginning was the Word.” The word for “word” is not simple. Perhaps it is best translated as “a reasonable expression.” We might say “In the beginning was the meaning,” or “the logic,” or “the reason,” or “the reasonability.” According to Church Fathers such as St. Athanasius (yesterday’s saint of the day), the creation resembles Christ in its rationality and intelligibility. “Through Him–through reason and in a reasonable way that communicates its own rationality–all things were made.”

The chant is inherently rational: it is composed of ratios and uses them in a meaningful way. It is also elevating. Unlike music bounded and confined by the limits of a chord progression, chant pursues the melodic line according to the meaning of the words. It is intelligible, amplifies the intelligibility of the words it accompanies, and pursues meaning. Singing it is a training in reason as well as in beauty and liturgical sense. Since the chant is united to Scriptural words almost exclusively, we hear the Word, the meaning, the truth, in many senses.

This is one of many reasons why it is essential for the Church that children learn to sing Gregorian chant at a tender age, when it can influence them. They receive moral strength from training in beauty, and intellectual strength and wisdom from rational exercise, in a connatural and deeply pleasurable way.