This is extremely interesting in many ways.

Midnight Mass, St. George Cathedral, Southwark, London

The schola director is Nick Gale.

The Mass was celebrated by His Grace Archbishop Peter Smith. The Mass setting (Gloria, Sanctus, Benedictus & Agnus Dei) was Nicholas O’Neill’s Missa Sancti Nicolai (2008) – Latin SATB (div) & organ. The Gregorian propers were sung (Introit, Alleluia and Communio – the Responsorial Psalm is sung in English), as was the Solemn Proclamation of Christmas (sung in English to the traditional, solemn Latin tone) and Credo III (sung in Latin). The Our Father was sung to the setting by Rimsky-Korsakov.

The communion motet: James MacMillan’s In splendoribus for SATB & trumpet. The Cathedral Girls Choir sang an anthem to Our Lady by Timothy Craig Harrison. The Mass concludes with Alma Redemptoris (simple tone sung by all).

The chant is free, natural, and strong – fantastic sound really. Incredibly, the people are actually singing, and not only the English hymns. Pay careful attention Americans: listen to the final Alma. Listen and weep for yourselves.

In general, Americans will learn a great deal just by watching these videos and seeing how it is done.

On that alto in the Shrine choir

GetReligion.org blogs on the WashPost story on Callista Gingrich.

Chant: The Master Path

DOCUMENT courtesy of NLM

Implications of a Centenary: Pontifical Institute for Sacred Music (1911-2011)

By Monsignor Valentin Miserachs Grau

President of the Pontifical Institute for Sacred Music

The Pontifical Institute for Sacred Music was founded by Pope Saint Pius X in 1911. The Papal Brief Expleverunt in which the new School was approved and praised is dated on the 14th November of that year, even if the academic activities had started several months before, on the 19th January. A Holy Mass to impetrate graces was celebrated on the 5th January. The whole Academic Year 2010-2011 has been dedicated to commemorate the centenary of the foundation of what was originally known as “Superior School of Sacred Music”, later included by Pope Pius

XI among the Roman Athenaeums and Ecclesiastical Universities under the denomination of “Pontifical Institute for Sacred Music”.

In the atmosphere of liturgical and musical renewal that characterized the second half of Nineteenth Century and in the frame of the research of the pure sources of Sacred Music that leaded to Pope Saint Pius X’s Motu proprio Inter sollicitudines [Tra le sollecitudini], it became evident it would not have been possible to carry on the programme of the reformation without schools of Sacred Music. It was within the Associazione Italiana Santa Cecilia (AISC) [Italian Association of Saint Cecily that the idea of settle a superior school in Rome, the most suitable place for that, as being the center of the whole Catholic world. From the first projects until the

opening of the School thirty years elapsed!

The Pontifical Institute for Sacred Music was foreseen since its very beginning –and it has remained substantially faithful to this vocation– as a centre of high formation specialising in the main branches of Sacred Music: Gregorian chant, composition, choir conduction, organ and musicology. It is not then about a conservatoire, with the study of different musical instruments, but about a university centre specifically devoted to Sacred Music. It is obvious, of course, that music in general underlies Sacred Music: in the course of composition, for instance, one must start, as in any conservatoire, with the study of harmony, counterpoint and fugue; then follow with the study of variations, the sonata form, and orchestration, before arriving at the great exquisitely sacred forms (motet, Mass and oratory). The Pontifical Institute has recently adhered to the Bologna Convention and has consequently adapted its own syllabus and courses to the new parameters proposed by it. It is in this spirit that a superior biennium of piano has been newly introduced, although this subject was already largely present as a complementary matter in our curriculum.

I should underline the fact that in the year just elapsed the Pontifical Institute has reached a historical maximum of students with 140 inscriptions, a third of whom coming from Italy and the remainder coming from the five continents. In addition to the study of the various musical disciplines, we have to record other exquisite musical activities like the beautiful season of concerts –with the relevant participation of our teachers and students– and, of course, periodical solemn liturgical celebrations in chant.

The Pontifical Institute for Sacred Music is not a body in the Church with normative character, but a school where to learn, with the study and practice, how to become leaven and a model for service to the different churches throughout the Catholic world.

In order to commemorate in a suitable way such an auspicious anniversary, we began by organizing the Concert season 2010-2011 according to the historical framework of these last hundred years, with reference to the subjects of our teaching, and to the most relevant figures that distinguished themselves in the life of the Pontifical Institute. I would like to mention the Holy Mass celebrated by myself in the Ancient Roman Rite in the church of Santi Giovanni e Petronio in the Via del Mascherone on the 5th January 2011, exactly as it happened a century ago, on the same day and in the same church, when our first president Father Angelo De Santi, S.I., wanted to open the activity of the infant school with a Holy Mass celebrated “in the intimacy”, with the attendance of a few professors and students. I have celebrated in the Ancient Rite both for historical accuracy and for giving joy to a number of professors and students that since some time ago asked me to celebrate the Holy Mass in the extraordinary form.

The most relevant acts took place in the last week of May: the publication of a thick volume entitled “Cantemus Domino”, that gathers the different and many-sided features of our hundred-year history; the edition of a CD collection of music by the Institute; the celebration of an important International Congress on Sacred Music (with the participation of more than one hundred speakers and lecturers), that was closed by an extraordinary concert and a Solemn Mass of Thanksgiving. During the Congress, three relevant figures related to Sacred Music were conferred with the honorary doctorate and held brilliant and highly-valued magisterial lectures.

I would like to underline that the Holy Father Benedict XVI has been in some way present in the centennial commemoration through a Letter addressed to our Grand Chancellor, The Most Eminent Lord Cardinal Zenon Grocholewski, in which His Holiness remembers the merits of the Institute along its hundred-year history and insists on how important it is for the future to continue working along the furrow of the great Tradition, an indispensable condition for a genuine updating (aggiornamento) having all the guarantees that the Church has always requested as essential connotations of liturgical Sacred Music: holiness, excellence of the forms (true art) and universality, in the sense that liturgical music could be acceptable to everybody, without shutting itself in abstruse or elitist forms and, least of all, turning down to trivial consumer products.

This one is a sore point: the rampant wave of false and truly dreadful liturgical music in our churches. Nevertheless, the will of the Church clearly appears in the words of the Holy Father I have just mentioned. He had already addressed to us in the allocution pronounced during his visit to the Pontifical Institute on 13th October 2007. Moreover, it is still fresh in our memory the Chyrograph that the Blessed Pope John Paul II wrote on 22nd November 2003 to commemorate the centenary of the Saint Pius X’s Motu proprio Inter sollicitudines (22nd November 1903), by which Pope Wojtyla assumed the main principles of this fundamental document without forgetting what the Second Vatican Council clearly expressed in the Chapter VI of its Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium on Sacred Liturgy. By doing that, Blessed John Paul II practically walked the same path traced by that Holy Pope who wanted his Motu proprio to have validity as the “juridical code of Sacred Music”. Now we must wonder: if the will of the Church has been clearly declared also in our times, how is it possible that the musical praxis in our churches distances itself in so evident a way from the same doctrine?

We must consider several problems at the root of this question, for instance the problem of repertoire. We have hinted at a double aspect: the risk of shutting oneself in a closed circle that would wish to essay new compositions considered as being of high quality in Liturgy. We must say that the evolution of musical language towards uncertain horizons makes the breach between “serious” music and popular sensitivity to become more and more profound. Liturgical music must be “universal”, that is acceptable to any kind of audience. Today it is difficult to find good music composed with this essential characteristic. I do not discuss the artistic value of certain contemporary productions, even sacred, but I think that it would not be opportune to insert them in the Sacred Liturgy. One cannot transform the “oratory” into “laboratory”.

The second aspect of the problem derives from a false interpretation of the conciliar doctrine on Sacred Music. As a matter of fact, the post-conciliar liturgical “renewal”, including the almost total lack of mandatory rules at a high level, has allowed a progressive decay of liturgical music, at the point of becoming, in the most cases, “consumer music” according to the parameters of the most slipshod easy-listening music. This sad practice sometimes determines attitudes of petulant rejection towards genuine Sacred Music, of yesterday and today, maybe composed in a simple manner, but according to the rules of Art. Only a change of mentality and a decisive “reforming” will –that I am afraid is far to come– would be able to bring back to our churches the good musical praxis and, together with it, also the conscientiousness of celebrations, that would not lack to entice, through the value of beauty, a large public, particularly young people, currently kept away by the prevailing amateurish practice, falsely popular and wrongly considered –even in good faith– as an effective instrument of approaching.

Regarding the power of involvement of which the good liturgical music is capable, I would like to add only what is my own personal experience. By a fortunate chance, I am acting after almost forty years, as Kapellmeister at the Roman Basilica of Saint Mary Major, where every Sunday and on feast days the Chapter Mass is celebrated in Latin, and with Gregorian and polyphonic chant accompanied by organ (and by a brass sextet in highest solemnities). I can assure you that the nave and the aisles of the basilica get packed and not rarely there are people that come after the ceremonies to express their gratefulness, moved to tears as they are, especially by the Hymn to the Madonna Salus Populi Romani (Our Lady, Salvation of the Roman People). They often cannot hold back the excitement and arrive to burst out clapping. People are thirsting for good music! It goes directly to the heart and is capable of working even resounding conversions.

Another compass of good liturgical music –always reminded by the Teaching of the Church– concerns the primacy of the pipe organ. The organ has always been considered as the prince of instruments in Roman Liturgy and consequently has enjoyed great honour and esteem. We know well that other rites use different instruments, or only the chant without any kind of instrumental accompaniment. But the Roman Church, and also the denominations born from the Lutheran Reformation, see in the pipe organ the preferred instrument for Liturgy. In Latin countries, the use of organ is almost exclusive whilst for Anglo-Saxon tradition the intervention of the orchestra is frequent in celebrations. This fact is not due to a whim or by pure chance: the organ has very ancient roots and has been praised along the centuries in the path of its historical improvement. The objective quality of its sound (produced and supported by the air blown into the pipes, comparable to the sound emitted by the human voice) and its exclusive phonic richness (that makes of it a world in itself and not a mere ersatz of the orchestra) justify the predilection that the Church fosters towards it. It is rightly so that the Second Vatican Council dedicates inspired words to the organ when stating that “it is the traditional musical instrument which adds a wonderful splendor to the Church’s ceremonies and powerfully lifts up man’s mind to God and to higher things” (SC, 120), in which it does no other thing that to recall the preceding doctrine both of Saint Pius X and Venerable Pius XII (especially in the splendid Encyclical Letter Musicae sacrae disciplina). By the way, I would like to remark that the publication of the PIMS that has got more success is the booklet Iucunde laudemus, that gathers together the most relevant documents of the Church’s Magisterium regarding Sacred Music. Just in these days, since the first edition was sold out, we have re-edited this work updated with further ecclesiastical documents, both from the preceding teaching and the one of the reigning Pope.

In our quick review of the main points underlying a good liturgical musical praxis, we have now arrived to a last but not least question, one that should be firstly considered: the Gregorian chant. It is the official chant of the Roman Church, as the Second Vatican Council reasserts. Its repertoire includes thousands of ancient, less ancient, and even modern pieces. Certainly, we can find the highest charm in the oldest compositions, dated back to the Xth-XIth Centuries. In this case also it has to do about an objective value, since the Gregorian chant represents the synthesis of the European and Mediterranean chant, related to the genuine and authentic popular chant, even that of the remotest regions of the world. It is a deeply human and essential chant that can be traced in its richness and variety of modes, in its rhythmic freedom (always at the service of the word), in the diversity and different degrees of its single pieces, according to the individual to whom the execution is assigned, etc. This is a chant that has found in the Church its most appropriate breeding ground and constitutes a unique treasure of priceless value, even from the merely cultural point of view.

Therefore, the rediscovery of Gregorian chant is a sine qua non condition to give back dignity to the liturgical music and not only as a valid repertoire in itself, but also as a source of inspiration for new compositions, as it was the case of the great polyphonists of the Renaissance, who –following the guidelines of the Council of Trent– created the structure bearing their wonderful works departing from the Gregorian subject matter. If we have in Gregorian chant the master path, why not follow it instead of persisting in scouring roads that in the most of cases drive to nowhere? But to undertake this work it is necessary to count on talented and well-prepared people. This is the goal of the Pontifical Institute for Sacred Music. This is because of these noble ideals that it fought along the last hundred years and will continue to fight in the future, in the conviction of paying an essential service to the universal Church in a primary field such that of liturgical Sacred Music. Saint Pius X was so persuaded as to write in the introduction of his Motu proprio these golden words:

Among the cares of the pastoral office, not only of this Supreme Chair, which We, though unworthy, occupy through the inscrutable dispositions of Providence, but of every local church, a leading one is without question that of maintaining and promoting the decorum of the House of God in which the august mysteries of religion are celebrated, and where the Christian people assemble to receive the grace of the Sacraments, to assist at the Holy Sacrifice of the Altar, to adore the most august Sacrament of the Lord’s Body and to unite in the common prayer of the Church in the public and solemn liturgical offices (…) We do therefore publish, motu proprio and with certain knowledge, Our present Instruction to which, as to a juridical code of sacred music, We will with the fullness of Our Apostolic Authority that the force of law be given, and We do by Our present handwriting impose its scrupulous observance on all” (Inter sollicitudines).

It would be desirable that the courage of Saint Pius X finds some echo in the Church of our times.

___________

Valentín Miserachs Grau is President of the Pontifical Institute for Sacred Music. He presented this address as part of the XXth General Assembly of the Foederatio Internationalis Una Voce

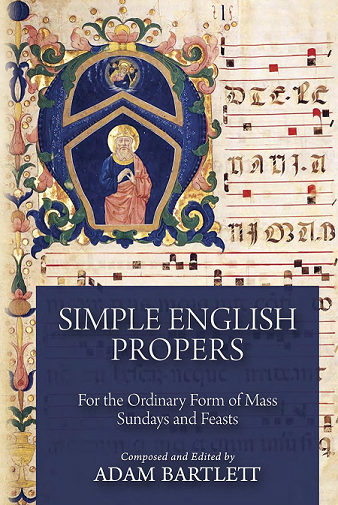

Last Chance to Be Part of the Greatest Book on Catholic Music Ever

Top Ten Things I’ve Learned about Sacred Music

Ten years ago, I knew next to nothing about Catholic music. I knew that something was not right in the parish music program. I had some sense that the fix for the problem was somewhere in our history and tradition, somewhere in some dusty books somewhere, and the answer surely had something to do with preconciliar practice. I intuited this just because the Second Vatican Council represented something like a gigantic shift, and older people reinforced this to me with harrowing stories of living through the turbulent times.

Beyond that, I knew very little.

What follows are the top ten things I’ve learned in the course of ten years of reading, singing, listening, and exploring. I offer them in roughly the order in which I discovered them for myself and in conjunction with working with others who pointed me in the right direction The point here is not only to share the lesson with readers but to admit to the existence of deep ignorance out there as regards Catholic music – and I know this because it was not long ago when I could be counted among the deeply ignorant. There is no shame in that. Admitting it is the first step toward shaping up.

In a lifetime of study, we could never know what we need to know, and relative to knowledge embedded in tradition itself, we are all hopelessly ignorant. This is also what makes Catholic music so exciting. There is always more to discover, always more to do. If you find a “know it all,” you can be pretty sure that he or she is a faker. We are all in the process of discovery. Here is my brief accounting of the high points I’ve gained from ten years in this process.

1. The Roman Rite comes with its own built-in music. This discovery came for me when I took at a look at the Gregorian Missal, which is a reduce and English-language version of the Sunday and feast day chants from the Graduale Romanum, which is the music book of the Roman Rite. I further discover that this book was not just old, though it is old; it is also new, with the latest edition having been produced in 1974 specifically for what is known at the ordinary form of the Roman Rite. This was an amazing revelation. It turns out that the Church does provide. The burden to cobble together music each week does not actually fall to us. In the same way that the books of the Bible are given to us, as is stable doctrine and moral teaching, the music is provided already in a perfect form for every single liturgical task. Our main task is to defer and master the ability to render it properly.

2. What we call hymns cannot be the main ritual music of the Roman Rite. Hymns play an integral role in the sung version of the Divine Office, but they are not part of the Mass. When they are used in Mass, they are more like medieval tropes, texts with music that elaborate on a theme. There is room for hymnody at Mass in particular places, but not as replacements for the real music of the Mass, except in extremely unusual situations. In general, all else equal, the chants proper to the ritual are to be sung. This is a great relief because I never liked the “hymn wars.” They are unnecessarily divisive and extremely subjective. It is best to bypass this problem altogether and sing the Mass itself.

3. The musical structure of the Roman Rite is both clear and stable. The main parts for the congregation are chants of the Mass ordinary: Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus Agnus. The congregation and schola are to sing the dialogues with the priest: greeting, memorial acclamation, and the like. The main job of the schola is to lead or sing alone the propers of the Mass: introit, Psalm and Alleluia, offertory, and communion. Beyond that, there are sequences. Until we can get this framework pounded in our heads, we will be lost and confused.

4. Nostalgia only gets you so far. The preconciliar past does not offer much in the way of a model to restore. A close looks shows that the propers at high Mass were sung to Psalm tones only but mostly people experienced low Mass with four hymns — just as we experience today. Hence many of the core problems we have today are inherited from the preconciliar practice. They had their “praise music” and we have ours; the main difference is the style of the times.

5. There was nothing wrong with the goals of Vatican II. A careful reading of the history shows that the fathers of this Council sought to fix the problem of the ubiquity of vernacular hymnody of Mass and sought to change some aspects of the liturgy in the hope of inspiring a fully sung Mass with Gregorian chant taking its proper place. Mistakes were made that unleashed the problem in way that no one even imagined before the Council.

6. It doesn’t take a big choir to do the music right. Motets and big polyphonic Mass settings are wonderful but they are not essential. The Church has given us 18 chanted Mass settings to chose from and they can all be led by a few singers or even one cantor. A big choir is a great thing but it is not necessary for a quality music program at a parish. Moreover, you are more likely to find yourself in the position of recruiting singers if the structure is already in place and there is some security and certainly over the task ahead.

7. Accompaniment is not required. Singing is music in the Roman Rite. Organ, piano, and guitar might not support singing; they might actually crowd it out.

8. A good default structure is more important than a huge repertoire. Every parish needs a reliable musical framework to fall back on for every Mass, so that it is not so dependent on a particular organist or choir leader or the presence of a large number of singers with a huge library of music. If this is done well, simple chants from the beginning to the end, combined with the beauty of silence, accomplishes the goal. And here is an especially good time to say thanks for the new Missal translation, which has all the music already given to us for the main parts of Mass.

9. You can’t blame the musicians for junky music at Mass. The Missal change quickly and hardly anyone was prepared. There were no books of English propers available until very recently. Musicians were using what they had and that was not much, and what has been available has been produced with very little understanding of the musical structure of the ritual. This problem has persisted until very recently.

10. Change does not come from edict. As much as we might dream of a pope or a priest who cracks down and demands appropriate music from everyone, this is not actually how change occurs. Change comes from patience, learning and teaching, inspiration and prayer, and hard work undertaken in the right spirit.

Those are my ten lessons. I have no doubt that the next ten years will continue to be fruitful no only in getting better at singing but in learning ever more about theory and practice of music in the Roman Rite.