Yesterday I found myself at a local megachurch for a convention that was being held there. As a music lover and an introvert, I studiously tried to avoid two things: the astonishingly loud and repetitive praise and worship music, and small-group discussions.

There was an older man sitting not far from me during a breakout talk, and I didn’t want him to think I was dismissing him by avoiding the discussions, so as the session ended I said hello. Turns out this was his home church, and since I am Catholic, he wanted to know two things: what books he could read on contemplative prayer, and how to pray the rosary.

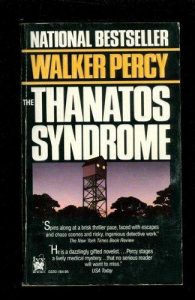

He made it clear that he did not want to become Catholic but said they don’t hear anything about contemplative prayer at his church, and wanted to know more about it. I told him about a lot of different authors from the Catholic mystical tradition. He settled on St. Teresa of Avila, and asked if there were a Catholic bookstore in the area where he could buy her books and a rosary. I gave a brief tutorial on the rosary, and we talked about asking for Mary’s and the other saints’ intercession, which he used to think idolatrous but now feels it is similar to asking a fellow believer for their prayers. We spoke until his wife called his cell, and said goodbye.

I have often felt that our efforts at Catholic evangelization aim too low. There has to be a “low door” for the unchurched seeker to enter, and thankfully we have good programs for that. But that simply cannot be where we stay. We have a journey to make, and that journey is serious and demanding, unchartable and rich beyond measure. We are all called to the mystical life. (A good book to read on this point is Fr. Thomas Dubay’s Fire Within.)

I learned a few things from the megachurch. They had excellent coffee and cookies. Their church members are dedicated to service, to the point of meeting very basic needs such as keeping restroom supplies stocked. Attention to these practical details makes for a very warm welcome. The music, while problematic on many levels, was very well produced. Our liturgical music, on the other hand, is often played and sung without a “reality check” such as a recording. Organists and singers in Catholic churches definitely benefit from hearing their own sound, correcting and polishing.

However, we as Catholics have much more important things to teach than to learn–if we haven’t forgotten them. And it sometimes seems as though we have forgotten. In some parishes, preaching rarely changes, and rarely has much content beyond the vaguely therapeutic message that God overcomes fear. This is inadequate. In a world hungry for spirituality, we offer a very weak tea, instead of the riches within our grasp and online for free: the Fathers, the Councils, the Rhineland mystics, the liturgical riches of the ancient hymns, St. Catherine and St. Therese, the lives of the saints, and ever so much more.

This morning, on the Feast of the Presentation, one of the giants of our mystical memory passed into eternal life. Fr. Kieran Kavanaugh, OCD, co-translated and annotated the Collected Works of both St. Teresa of Avila and St. John of the Cross. Fr. Kavanaugh labored to make the writings of these Mystical Doctors accessible, in all their richness, in flowing English of the present day. Here is an example from St. John’s Spiritual Canticle.

My Beloved, the mountains,

and lonely wooded valleys,

strange islands,

and resounding rivers,

the whistling of love-stirring breezes,the tranquil night

at the time of the rising dawn,

silent music,

sounding solitude,

the supper that refreshes, and deepens love.

May Fr. Kavanaugh, and all who guide others along the paths of contemplative prayer, be blessed themselves with the beatific vision, and union with God. May he rest in peace.