To not sing “Magnificat?” Unimaginable! We must “Collect” ourselves.

Realizing that our friends’ voices over Fr. Ruff’s blog still continue to re-voice the sentiments and protestations that continue to bubble up among primariy the non-American English conferences regarding the reception and adoption of the third edition of the Roman Missal translation, I thought a few choice quotations and reflections from our equally loyal opposition might be beneficial to the vitality of the dialogue.

In the October edition of the periodical “MAGNIFICAT” (Oct.2011, Vol.13, N.8), Professor Christopher Carstens (visiting faculty, Liturgical Institute, Mundelein, IL:., director of the Office of Sacred Worship, La Crosse, WI.) added an essay to an ongoing series about preparing for the implementation in the states, “The Roman Rite’s Collection of Collects.” As the current gauche phrase goes “You had me at….,” Carstens’ first line, the famed quote of Augustine “Singing is a lover’s thing,” certainly piqued my interest. He then reminds us that in worship we, the Bride of Christ, “sings from her heart to her loving bridegroom, Christ the Lord.” He continues, “From the Introductory Rites (of the MR3) of the beginning of Mass, the Church prepares the faithful to join in this great song of love.”

Now I’ve personally been reminded and scolded that being a career pastoral musicians does not me a liturgist make; I’ve got that. But in musicans’ defense, is there another, more apt way to engage in a deliberation of the affect of this expression of sacral love and language in the din of the recent debates? Carstens invites us to listen for three particular aspects of the Collects, the first of which is “The Structure of the Collect.” As just a teaser I’ll report that he outlines: 1. the address; 2. a short relative clause describing God; 3. the petition itself; and 4. the conclusion addressed to the Trinity. He then claims this structure “connects each thought, sentiment, and petition back to God….” whereas in previous editions most Collects use two sentences rather than this series of phrases within one, which he concludes “leads us and our intentions more directly back to God.”

The next aspect he comments upon is the “Language of the Collect.” Carstens restates much of the obvious intentions behind MR3, again much deconstructed and debated here and elsewhere, and presumably familiar to liturgy blogophiles. But it is important to note that many, if not most, subscribers to the “Magnificat” periodical likely fall outside that demographic. So he emphasizes “value and importance” to the traits of “linguistic register.” Carsten points out that every person “employs different registers on a daily basis.” As much as I would love to associate the word “register” to its most musical interpretation, Carsten simply means how “we speak to our pets, our friends, our bosses, our loved ones, our slow computer, and our God…” How simple, how elegant a depiction of the importance of the “tone” (pun very much intended) with which we unfold the language of love to our Creator. And paradoxically, how often all of us seem to impugn a negative “tone” in our internet discourse without first thinking that we really cannot “register” our expressed thoughts audibly in this medium.

The author then illustrates this aspect by citing the Collect from the Vigil of Pentecost. Towards the singer and poet in us all I will skip his exegesis that clearly portrays the relationship between translation and register and get to a specific example he cites. The Latin “contineri” he says “could be translated “surrounded” or “contained.” But he offers that “encompassed, though, is a more extraordinary term…evoking for the reader (I wish he’d said ‘listener’ instead) the image of a compass, pointing to all directions…” I would ask the singer in each of us, before deciding upon the richest depiction of how far the Paschal Mystery extends out from Calvary’s cross, to audition: “surrounded….contained……encompassed.” Which is the symbol crying to be sung?

Finally Carstens lists the third aspect, “The Sources of the Collect” as they are presented to us from scripture and tradition. He alludes the Collect for the 20th Sunday of Ordinary Time to St. Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians in which the apostle reminds us “What eye has not seen, and ear has not heard, and what has not entered the human heart, what God has prepared for those who love him.” The Collect now is rendered “O God, who have prepared for those who love you good things which no eye can see, fill our hearts, we pray, with the warmth of your love.” He infers that this Collect intones the Pauline excerpt literally almost verbatim. He declares “The ‘vernacular’ of the Church….is Scripture: especially at prayer, it is Bible that is spoken.” (Again, I wish he’d used “sung” rather than “spoken.”)

In this brief article I believe the professor argues for the nuance and registral context of language “off the page” to be fulfilled best within the union of poetry and song, the singularly unique sacral language, not music, that is the heart of chant. If, as he asserts, we are attentive as a start to the structure, and then to the richness within the language used, and its sources, then we can better enjoin our voices in “the eternal song of love between Bride and Bridegroom, the Church and her Lord.”

A couple of post-scripts: I believe this is also a concept that is shared by Dr. Paul F. Ford in his presentations to clergy and laity regarding the Missal implementation. If celebrants accept the clearly stated intent (just check out the default settings of all orations in the new editions of subscription missals!) that they, at least, acknowledge that by chanting this orations and Collects, they are most effectively abetting full, conscious and active participation of all the gathered Faithful at Mass.

Secondly, it’s somewhat ironic that this muse struck me this evening as I have been seriously contemplating taking a “sabbatical” from blogdom and forums on the WorldWideInterLinkCyberWebs! There seems to be a great confluence of increased rancor, whose tone is unmistakeably contentious, as well as a movement of a great number of major blog authors to new domains. I’m still undecided, but I think I need to take a breather for a while, my friends. Thank you for putting up with the barrage of verbiage for so long.

Where the Vatican Stands on Liturgy and the Extraordinary Form

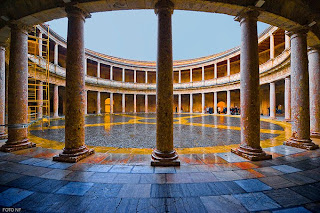

Singing in Granada

I have writer’s block as I try to revise part of my doctoral dissertation. So to be inspired, I decided to take a little trip to the beautiful city of Granada in the south of Spain. This legendary city, made famous by the Muslims, was the last Muslim stronghold to yield to the Reconquista of Ferdinand and Isabel the Catholic. It was certainly amazing to kneel and pray before the tombs of the Reyes Catolicos, and I fondly remembered there Dr Warren Carroll, the founder of Christendom College, my dear alma mater. It was Dr Carroll who set many a young Catholic mind ablaze with the feats of Isabel the Catholic, and I am sure that she is interceding for him as he recently passed away.

More Thoughts About Communion Under Both Kinds

During the late Middle Ages, the Western liturgy developed in such a way as to radically alter the way in which people received Holy Communion, compared with how they did so in the first millennium of Christianity. In many places Communion became less frequent, and the Sacrament of Holy Communion was often separated, not only conceptually but physically, from the Sacrifice of the Mass. As a theological development, it was certainly useful to make distinctions between Sacrifice and Sacrament. But often the Sacrifice was exalted to the detriment of the Sacrament. The mode in which Holy Communion was received gradually began to change. Communion in the hand had already long been replaced by Communion on the tongue. Communion standing was replaced by Communion kneeling. And the reception of the Precious Blood from the Chalice gradually disappeared. Eventually, these organic developments were recognized in local liturgical laws and customs.

At the Council of Trent, the Catholic Church felt the need to state clearly the Church’s understanding of the Sacrifice and Sacrament. That re-presentation of the Church’s teaching could not but raise questions about the practical ways in which Sacrament and Sacrifice were celebrated in the Church. One of the principal complaints of the Protestants was that the faithful had ceased to receive from the Chalice. At the Council of Trent, there was serious discussion as to whether the Council should restore the Chalice to the faithful. The fact that the Council discussed such an important issue is instructive. First of all, it signifies that, since it could be discussed at all, reception of the chalice by the faithful was not considered in itself against Catholic teaching on the Eucharist. Second of all, it was one of the first times that an ecumenical council would deliberate on a practical liturgical issue in such a way as its decision would be considering binding on the whole Church. The gradual spontaneous development of liturgical law and custom was held to be insufficient in the face of the Reformation to preserve the unity of Christians in conformity with Catholic doctrine.

The Council came to the decision that restoration of the chalice to the faithful would not be opportune at that time and would create confusion as to what Catholic teaching really was. In doing so, the Council created a precedent: ecumenical councils could decide on practical matters of the liturgy and bind the Church as to their decision. As Pope St Pius V implemented the Council of Trent, the extension of the Missal of the Roman Curia to the entire Western Church sought to ensure doctrinal unity through the unity of liturgical practice reflecting that unity.

As is well known, the theological developments of the twentieth century, together with the Liturgical Movement, built on the distinction between Sacrament and Sacrifice as elaborated in the Medieval and Baroque periods while contextualizing them in a way as to restore a greater unity to Sacrament and Sacrifice. When the Second Vatican Council came around, the gradual centralization of liturgical practice was such a given that it was not considered strange at all that an ecumenical council should debate how to integrate these theological developments into the liturgical life of the Church in a way which would be binding for the whole Church.

At Trent, the Fathers of the Council were afraid that restoring the Chalice to the faithful would give raise to a very bizarre notion of the Eucharist. The Reformers protested that the Mass was a memorial, a sacrifice of praise, and as such, the sacrament related to the sacrifice of praise was also memorial. While they often disagreed with each other as to the actual mode of presence of Christ in the Eucharistic species, they all held to the belief that the separate words commemorating what the LORD did at the Last Supper indicated that one received the Body and the Blood of Christ, but as a memorial (NB Catholic doctrine considers it a memorial as well, but much more). The Catholic Church countered with a more coherent metaphysical argument based on how she definitively interpreted the mode of Christ’s presence: if the bread and wine were changed into the Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity of Christ, then the separate consecration of the elements, in obedience to the LORD’s command, did not detract from the underlying reality that one received, not just the Body or the Blood of Christ as a memorial, but the entire Christ, really, under either species.

At Vatican II, the Fathers of the Council perhaps took for granted that the teaching of the Council of Trent was so rooted in the faithful that the danger of a Protestantizing effect on them by the reception of the Chalice had passed. Catholics were sure that the careful metaphysical elaboration of Eucharistic doctrine at Trent had been received by the Church in such a way as to be rock solid. Therefore, a return to the Chalice would not endanger in any way orthodox faith in the Eucharist. On the contrary, it might actually increase Eucharistic fervor.

Of course, at the same time theological and liturgical developments were placing the doctrine of Trent in a richer biblical, ecclesial and historical context, there were also other currents going on in the Church. Two of those are important for our discussion here. First, there was much discussion on how to explain the mode of the presence of Christ in the Eucharist without reference to a metaphysical framework crafted almost entirely in Aristotelian categories. Many of those theories which were very much in vogue during the time of Vatican II are all but forgotten now, but they were enough of a possible threat to the balance of Catholic Eucharistic doctrine for Paul VI to re-propose the perennial teaching of the Church in the Credo of the People of God, Ecclesiam suam and Mysterium Eucharistiae. Second, there was much discussion on the history and objective constitution of the Sacrament of Orders, particularly as related to the newly found enthusiasm for the apostolate of the laity. Some of the more fanciful attempts at blurring the distinction between the ministerial priesthood of Orders and the common priesthood of Baptism had already been staved off by Vatican II’s insistence that the difference was an essential one, but thinkers continued to propose that the distinction should be blurrier than it actually was made out by Vatican II to be.

The evaluation of the entire post-conciliar Liturgical Reform, in general, and the restoration of the Chalice to the faithful, in particular, must be had holding these two historical trends in mind: doubt as to the exact mode of the Presence of Christ in the Eucharist and as to the distinction between the ministerial and the common priesthood. Even though the Magisterium was to clearly state the difference between the various modes of presence of Christ and between the two types of priesthood, there still continues to be in certain quarters of the Church a confusion about the distinction which is deliberately advanced by some who do not agree with the distinctions.

Into this mix there came the permission of Paul VI to depute certain lay faithful to be Extraordinary Ministers of Holy Communion. Just as with Communion under both species, the existence of laity distributing Holy Communion under certain conditions (for example, persecution) was not unknown. The documents the Magisterium has crafted that pertain to these Extraordinary Ministers have reiterated the teaching of the Church as to the nature of the distinction between ministerial and common priesthood and the modes of the presence of Christ in the Eucharist.

However, the widespread deliberate obfuscation of the clarity of the Church’s teaching on these points has continued even as the Church’s carefully worded laws as to the employment of Communion under both species and Extraordinary Ministers of Holy Communion have been ignored.

It must be said at the outset that Communion under both species and the Extraordinary Ministers of Holy Communion do not in themselves prejudice the perennial teaching of the Catholic Church on the Eucharist. But against the background of a confusion as to the modes of presence of Christ in the Eucharist and the distinction between ministerial and common priesthood, these two issues have created situations in certain places of a very real confusion as to the basic teaching of the Church on the sacraments.

Confusion as to the modes of the presence of Christ has resulted in a leveling of the distinction of the virtual presence of Christ in the assembly and the Scriptures, for example, and the real presence of Christ in the sacred species. The result is that for some, the Sacrifice of the Mass has taken on a distinctively more memorial tone, and as such is not qualitatively much different than the reading of Scripture or prayer among believers. The Sacrament of the Eucharist then becomes a memorial at which the important thing is the re-presentation of what Jesus did at the Last Supper on Maundy Thursday, and not the underlying metaphysical reality of the reception of the whole Christ under either species seen in a unity with the mysteries of Good Friday and Easter.

Confusion as to the distinction between the ministerial and common priesthood has resulted in a situation in which the distribution of Holy Communion is seen merely in functionalist terms on its own merits and not in the context of a richly symbolical grammar. Thus, practical concerns as to the efficiency of distributing the Sacrament, seen as effect of a memorial and not as fruit of the Sacrifice, take priority over any symbolic or hierarchical grammar by which the Sacrifice-Sacrament relation has always been understood by the Magisterium. Add to this the contemporary concern for political equality which abhors distinctions as prejudicial, and a language of rights, and thus some Extraordinary Ministers see themselves as having a right to exercise a ministry within the Church and some Faithful then see themselves has having a right to receive Communion, just as the priest does, under both species.

Again, let it be said from the outset that there are Extraordinary Ministers of Holy Communion and Communicants whose faith is entirely coherent with the teaching of the Magisterium. But there are also those whose faith is not. The fact that the Church has not commanded the habitual reception of Holy Communion under both species and the use of Extraordinary Ministers, but on the contrary has very specific laws as to when they can be employed, is consistently ignored in many parts. Yet it also must be noted that there are many places within the Church Universal where Communion under both species and Extraordinary Ministers continues to be rare if not non-existent.

The Bishop, who is responsible for making sure that the Liturgy of the Church in the his diocese is celebrated in conformity with the teaching of the Church and with liturgical and canon law, is ultimately responsible for making sure that the confusion over the modes of presence of Christ and between the ministerial and common priesthood does not distort the legitimate employment of Communion under both species and Extraordinary Ministers. Also, it certainly may be considered to not be odd for a Bishop to wish to bring the practice of his diocese in line, not only with Catholic teaching and canon law, but also the practice of the greater Church at large.

To my knowledge, in most countries around the world, Communion under both species and the use of Extraordinary Ministers of Holy Communion is rare indeed. Their use, in contrast, is not only common, but perhaps even exaggerated, in the English and German speaking world, precisely where the confusion over the modes of the presence of Christ and the distinction between ministerial and common priesthood is the greatest. While it is true that abuse does not take away use, it is understandable when a Bishop orders that the practice of a particular Church conform to what is the practice of the universal Church as well as to the theological, liturgical and canonical norms of the Magisterium.

All of this until now has been very theoretical. But why would a Bishop be tempted to govern his diocese in such a fashion as to end the practice of something which, even if it is rare universally, is accepted locally, and also allowable by the Church’s law? Perhaps it is useful to document some of the things that one often hears around Catholic parishes in the United States on Communion under both species and Extraordinary Ministers of Holy Communion. I have heard all of these things at one time or another.

1. When I don’t receive Holy Communion, I feel like I haven’t been to Mass.

2. When I don’t receive the Precious Blood, I feel like I have been cheated. I haven’t really received Holy Communion.

3. Why is there no more wine at Mass?

4. I just want to give Communion out at Mass. That way I can be involved in the Church and involved in the Mass.

5. I have a right to be a Eucharistic Minister in the Church.

6. You be Bread and I’ll be Wine. Host Station and Wine Stations.

7. Are there enough breads in the tabernacle?

8. Father, why didn’t you consecrate enough wine? We didn’t have enough wine at Mass and I wasn’t able to receive it.

9. I have a gluten intolerance, so I have to get the wine.

10. The decision to take away Eucharistic ministers and the wine is pre-Vatican II and is offensive to Protestants.

11. The only way women can participate in the Church on the Altar is as a Eucharistic Minister.

12. Just because I am divorced and remarried doesn’t mean I shouldn’t be a Eucharistic Minister.

13. I know my child doesn’t go to Mass and we’re Lutherans, but why can’t she be a Eucharistic Minister at the School Mass in her Catholic school? Isn’t that exclusive?

14. Father didn’t wake up in time for Mass, so we just did a Communion service.

15. I like Sister’s Mass better than Father’s. Well, it’s not a Mass, but you know what I mean.

I will not attempt to analyze each statement, but make some general observations germane to all of them. One of the most fascinating aspects of modern theology and the classical Liturgical Movement was to reunite Sacrifice and Sacrament where post-Tridentine theology has made them conceptually distinct. Yet the experience of the post-Vatican II Church has been a separation of them once again. Despite Pope Pius XII’s warning not to separate Altar from Tabernacle, that is precisely what has happened after the Council: Sacrament and Sacrifice lose any visual relationship with each other. For many people, the Mass has become a means to the end of producing Holy Communion. Yet the Mass, which is the perfect prayer of self-offering of Jesus to His Father in the Holy Spirit, has an infinite value of itself. Participation in the Mass as a Sacrifice is not made any more perfect by participation in the Mass as a Sacrament in Holy Communion. They are two different modes of participation, just as participation is both internal and external. They are ordered to each other, but one can be had without the other.

Another interesting observation to make is that there is a practical denial of the fact that sacramental communion presupposes ecclesial communion. One does not receive or distribute Communion by right, merely by the fact of being present at a celebration of the Mass in a Catholic Church. One receives Communion as a privilege, and only after being properly disposed. The proper disposition to receive Communion is indicated by Divine Revelation (discerning the Body and Blood of the LORD) and canon law. Furthermore, the reception of Communion is a protestation of faith and a public act of worship. As such, Communion is not the place for arbitrary and individualist deviations from the norms. Sacramental Communion must take place in the fullest harmony with ecclesial Communion. As such, it is a powerful antidote to the atomistic individualism of our times.

Also, the reduction of the Mass to its commemorative aspect or to its aspect as meal has some Catholics acting as if all they receive when they received the consecrated bread is the Body of Christ, as if that were somehow the flesh and bones of the LORD, and the consecrated wine is the Blood of Christ, as if that were somehow just the red liquid. Actually, this presents a gross misunderstanding of the Eucharistic species. It does not take into consideration the doctrine of concomitance by which the whole and entire Christ is received under either species. Because of the Resurrection of the LORD, since His Body and Blood are reunited with His Soul and Divinity, when the Catholic receives the Eucharist, he receives the Risen Christ. The distortion of this truth is particularly worrisome. First of all, it makes the Catholic doctrine on the Real Presence metaphysically incoherent. Second of all, it makes the Mass seem like nothing other than receiving two things separately as the Body and Blood, Soul and Divinity of the LORD were separated on Good Friday. Third of all, especially given the post-Vatican II emphasis on the Mass as Paschal Mystery, the reduction of the Mass to the commemoration of Holy Thursday seen against the backdrop of the separation of the Body, Blood, Soul and Divinity of Christ on Good Friday, without a real frame of reference to the Risen Christ, is ironic. It also caters to the Protestant caricature of Catholic worship as entirely Good Friday centered and not Paschal in its understanding. It levels out the intimate connection between each moment of the Paschal Mystery as present in the Eucharistic species and celebration, and as such, is a betrayal of the advancement of Eucharistic and liturgical theology in the last century.

The referral to the Sacred Species solely by their accidents, namely bread and wine, after the Consecration, is so common as to be unnoteworthy. But it is also imprecise. Often when I have sought to correct someone who insists on calling the Species bread and wine after the Consecration, they will respond, “Well, Father, you know what I mean.” But is such an attitude towards the elements not closer to consubstantiation or some form of impanation, which is inconsistent with Eucharistic doctrine?

Finally, a reduction of the concept of participation to a merely external one in which everyone should be made to participate as much as possible with no reference to the teaching of the Church on the distinction between ministerial and common priesthood also emphasizes the Mass as a means to an end of receiving Communion and separates Sacrifice and Sacrament. It has been suggested in some quarters that, because the Eucharist is so important for the Christian life, that married men or women should be ordained to the priesthood or that the laity should be able to preside over the Eucharistic synaxis. Now, while it is possible for married men to be ordained to the priesthood, the Church has reiterated that she does not have the power to ordain women to the priesthood. The suggestion that the laity preside over the Eucharistic synaxis denies the essential link between Holy Orders and the Eucharist, and is the fruit of the blurring of the distinction between the ministerial and the common priesthood. The sacramental economy is divided against itself, where there is a profound unity of divine design. It also promotes a functionalist and utilitarian approach to the sacramental economy, where efficiency, political correctness and convenience are the prized categories, and not theological ones.

Now, none of the above fifteen statements was uttered by anyone who has any malice towards or bone to pick with the Church. The people I know who have said the above statements are frequent, even daily Mass-goers, who love their Church and are ready to make personal sacrifices for their faith. But, as we have seen, it is precisely the fact that these problematic statements are common on the lips of the faithful which leads us to question: Have we truly imparted to our people the fullness of the Church’s teaching on the Eucharist? Of course, the Church’s teaching is much richer than the few elements highlighted here. The Eucharist has profound implications not only for the spiritual life of the individual Christian, but for the entire world and social order.

As we have seen, the terrible confusion in the Church on the Eucharist is not directly the result of the permission, under certain circumstances laid out by canon law, for Communion under both species and Extraordinary Ministers of Holy Communion. But the theological confusion over the modes of the presence of Christ in the Eucharist and the distinction between the ministerial and ordained priesthood has been conveyed to the faithful in part through those vehicles. It is up to individual Bishops to discern whether it is prudent or not to go back to basics, and then assure that the use of Communion under both species and Extraordinary Ministers of Holy Communion is not distorted by questionable theology. And when the basics are clear, those two issues cease to have the monumental import with which they have been invested by those who use them as chess pieces in a strategy to reinterpret the Church’s teaching on the sacraments.

NB. By means of offering a resource of relatively recent theology which makes accessible the Church’s teaching on these matters, I recommend Abbot Vonier’s A Key to the Doctrine of the Eucharist.

Sale on Hayburn Masterpiece

On a person note, this was the book that turned everything around for me. It is absolutely amazing.

What about the “Grout” Mass approach?

Back in the day, er, around the turn of the century, there was a certain amount of interest expended within NPM and other places about Monsignor Francis Mannion’s writings on identifiable modalities that liturgical musicians used typically to program Mass repertoires. One of those models I recall Monsignor wasn’t so keen on was “Eclecticism.” I remember at Indy 99 NPM there were two sessions inwhich that model and the others received spirited debate and deconstruction. But as I listened, I knew that I still regarded “eclecticism” as a defendable and even beneficial philosophy for a parish that had the abilities to adequately perform diverse repertoires. Now by “eclectic,” I don’t mean that various Masses in a parish weekend feature one style at a particular time, another elsewhere. I do mean the deliberate use of diverse styles and forms within a single Mass by a capable ensemble or even song leader/accompanist.

Back in the day, er, around the turn of the century, there was a certain amount of interest expended within NPM and other places about Monsignor Francis Mannion’s writings on identifiable modalities that liturgical musicians used typically to program Mass repertoires. One of those models I recall Monsignor wasn’t so keen on was “Eclecticism.” I remember at Indy 99 NPM there were two sessions inwhich that model and the others received spirited debate and deconstruction. But as I listened, I knew that I still regarded “eclecticism” as a defendable and even beneficial philosophy for a parish that had the abilities to adequately perform diverse repertoires. Now by “eclectic,” I don’t mean that various Masses in a parish weekend feature one style at a particular time, another elsewhere. I do mean the deliberate use of diverse styles and forms within a single Mass by a capable ensemble or even song leader/accompanist.So, let me show the scaffold of a so-dubbed eclectic Mass music order:

*Introit: chanted in either Latin or the vernacular from any number of sources, in coordinated combination with:

*A congregational Entrance Hymn/Song, propers-based, scriptural allusion or action designated.

*A chanted Kyrie (Greek/vernacular) accessible to PIPs.

*A polyphonic, strophic or choral Gloria, accessible to the congregation according to the setting.

*The responsorial of the day from the psalter of the hymnal/missal at use in the parish; a chanted simple version such as AOZ is compiling, or a vernacular version or emulation of the gradual.

*Gospel acclamation: same criteria as the psalm

*Offertory: probably the most variable moment for options-

Hymn/Song of the day approach

. Choral Motet or anthem, either verbatim from the Offertorio or scriptural allusion

Chanted Offertorio in Latin/English

Strophic version such as found in Simple Choral Gradual

*Sanctus/Memorial/Amen- I believe that whatever style or form, these three should be uniformly related.

ICEL/Jubilate Deo/Graduale Ordinary Chant settings/”new chant” ala St. Sherwin/Arrowsmith

Chant-based emulation- The Lee setting, Proulx’s Simplex, Psallite (Ford), Warner “Charity&Love”

Homophonic: Schubert/Proulx “Deutsche,” O’Shea “Mediatrix,” Proulx “Oecumenica” etc.

Others that do not juxtapose or challenge the sensibilities of the mix of styles: such as using a Leon Roberts Gospel setting, or a setting that is mechanical or simplistic that bespeaks a “utilitarian” rather than artistic merit. That, of course, is a taste-based assessment, so if I say I’d choose an Andres Gouze setting over Proulx’s “Community,” well, that’s how I’d make the judgment call. I also believe in a necessary priority of actualized, sung participation of all the faithful for the Sanctus, which second to the Pater Noster and collect responses, I believe is afforded to the congregation by Musica Sacram as a rightful priority. The occasional employment of a polyphonic or other classical choral Sanctus as is practiced by Prof. Mahrt twice or so per year doesn’t intrude upon that maxim seriously.

*Lamb of God/Fraction – I’m partial to either

a chanted version in Latin/vernacular, or

a superb choral version, either language option, of appropriate duration

*Depending upon the number of congregants, priests/deacons, EMHC’s and whether Eucharist is offered and received under both forms-

The chanted Communio of the day, whether from the GR, or from other revised/alternative collections

The homophonic or metered Communio from composers such as Rice, Tietze, P.Ford etc.

Alius cantus aptus versions closely aligned to the Communio that are worthily set.

A polyphonic Communio which either/all then could transition to a

*Communion processional hymn/song/antiphonal psalm setting.

I’m going to cut off my remarks here, as the issue of whether to program special choral pieces prior or after the Communion prayer is sung by the celebrant is generally a local issue, not to mention the specific need for silent prayer and contemplation. And the choice of using a sung dismissal hymn or song versus an organ or instrumental postlude, or even silence is also a local issue.

So, what are the holes in approaching programming an order of music in the survey, or Grout mode?

Do tell.