When my Peruvian friend Guillermo suggested we go to the Cathedral of Pamplona to pray the Rosary last Saturday night, neither of us knew what to expect. Both of us had the experience of coming across people who were constantly asking us, “Are you going to the Rosario de los Esclavos?” as if it were a big deal. Cynic that I am, I thought we would mumble through five decades of the rosary like the Irish washerwomen before Low Mass in olden times, and then we could afterwards be off on our merry way to have a nice glass of Rioja and debate theology in the Plaza del Castillo so loved by Hemingway. Was I wrong!

The Esclavos who were “animating” the Rosary are actually a pious association of the faithful, to use the modern canonical jargon, whose origin is really rather lost in the midst of time. They have been saying the Rosary every night in the Cathedral of Pamplona for so long no one seems to be bothered with asking how long they have been doing it. Maybe I have some residue from being raised as a Baptist, so the thought of slaves of Mary, I found a little, well, interesting. And being raised in the South, the idea of slaves of Mary was even more perplexing. But thank God the Hispanic world does not revolve around my complexes, and it is much the healthier for it. Pace to fans of St Louis Grignon de Montfort who read this blog! The point is that the Slaves of Mary love their Mother, and on the last Saturday of October, the month STILL dedicated to Our Lady (pause for liturgical Nazi rationalist shivers up spine), I was in for a treat.

At precisely 1930 hours, a bell rang and a procession made its way to the Altar. The banner of the Immaculate Conception flanked by two candles headed up the procession from the neo-Rococo riot of a sacristy through the stately Gothic nave into the walled and gated Quire where the solid silver canopy topped by a caped and mantilla-clad Virgen y Niño presided over a silver altar which looked curiously like a pulpit with a top on it. But behind it was a procession of young people, sweatshirt and jean uniformed, each with an enormous lantern encased in stained glass, each one representing a mystery of the Rosary. At the end of the Procession, the Archbishop in green cope, mitre, and crosier, accompanied by altar boys in cassock and fine lace surplices and two canons with their flat Spanish birettas and red pompoms and red and black mantelletas.

The Archbishop and Canons went to the Throne, inside of the gated sanctuary, and the World Youth Day-meets-Baroque Spanish Catholicism adolescents lined up in front of, but outside of the sanctuary. A men’s choir on risers to the left of the Quire sang.

¡Enhorabuena! This looks promising, I thought. The Rosary began as normal. Four mysteries were prayed, with the people saying the first part and then a cantor the second part of the prayers for one mystery and then reversing for the next one. Right before the Gloria Patri of each mystery, a bell was rung by one of the men in the choir to remind everyone that the mystery was about to close. After each Mystery, the Choir sang a brief responsory together with the people. Because this looked like just another Rosary in church, but a little “souped up,” I took advantage of the presence of Monsignor Canon Penitentiary’s presence to go to confession. As I left, it was time for the Fifth Mystery.

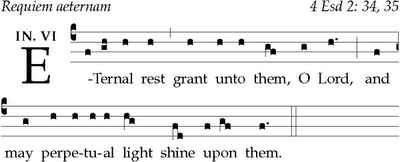

Not more of the same. Not at all. A bell rang, and a procession began again. A large float on wheels, with yet another image of the Blessed Virgin, deftly managed by an older gentleman came out of nowhere, and the entire Procession lined up in the middle of the Ambulatory. Behind the Archbishop, the little kids from the parish came with their own smaller lanterns with clear glass covers. The Choir started to sing the Pater Noster in Spanish, but in four-part harmony. Then, the laity nonchalantly arranged themselves in two lines parallel to the central line of torchbearers and clergy, and, after another bell, everyone started walking through the Ambulatory. The Ave Maria was sung ten times in Spanish, the choir singing the first part and the people the second part. All in perfect and well done four part harmony, and accompanied by organ improvisations. The Gloria Patri was sung in a similar way. Another bell rang, and the Procession stopped for a statio. A hymn to the Blessed Virgin was sung by the Choir, and then the Litany of Loreto, this time in Latin and in four part harmony between choir and people. The Procession returned to its place at the beginning of the Rosary, and the Archbishop gave a brief fervorino about the place of Mary in the New Evangelization. After the blessing, an Organ Recessional accompanied the participants back to the sacristy.

Some observations. It was striking that there was not one “worship aid” to be found anywhere, there was no one greeting the people or barking out instructions in an officious manner, there was not one glitch in the procession. There was no need. It had been done this way for God knows how long, and it had never been touched. And it also meant that someone like myself, who had never seen this done, could participate in it fully with no problem. The repetition of the music throughout the Rosary and the easily melodies meant that I could catch on quickly, and the movements were all intuitive and well executed, without being exaggerated, militaristic, or staged.

There was also none of the modern attempts to “evangelise” or “modernise” the proceedings, as has been done to so many such pious devotions in other places in Europe. No forced Liturgy of the Word, no tiresome explanations about devotions having second place to the Eucharist, no boring sermonizing on current events.

The young people were involved, not by making it “cool and relevant” by an older generation who still think they know what young people want. They were just involved. Period. And they loved it. What a hoot to hear some of the young men joke about going to the gym to get pumped up so they could carry these heave torches like men, or the young ladies appreciating the colors in the stained glass globes of their torches! The whole Church was involved: from the little ones with their little torches to the old men in the Choir, to the Archbishop. There was not a soul who was excluded, and no one was forced to do anything either.

There was also no allergy to multiplication of images, as there were two in procession. And it was also not a clergy-led event. Neither the Archbishop nor the Canons nor the diocesan clergy felt the need to change how the Rosary was done, or preach at the faithful about how “unmodern” it was until they stopped going to it all. No clericalism, of the clerical or the lay variety, here.

The fact that, during the first four decades of the Rosary, no one could see the Archbishop and Canons for the torchbearers standing in front of a gated sanctuary where visibility was practically nil, did not seem to bother anyone. The lack of visibility was made up for by the procession during the last decade. And the pilgrim Church on its journey was well symbolized by the stately procession, fully accompanied by the people, through the Church.

Guillermo made the interesting comment, “You see how Baroque Catholicism attracts people.” I was surprised to hear his observation framed in these terms. The cathedral was comfortably full, and there were not only young people, but people of all ages, together. And everyone had something to do, and they did it without prompting, and without practicing, either. It was all part of a received heritage. This type of Procession does hearken back to Baroque Tridentine piety, the same kind of devotional life that liturgical dilettantes and self-proclaimed experts have been trying to extirpate for years. A feast for the senses, with music which was not artsy or folksy, but eminently singable and beautiful.

To participate in such a devotion makes me realize how, in America, our worship is very cold and sterile. For all of the attempts to make people “feel at home” and make “Church into community”, so often it just seems like so much blah-blah-blah, incessant talking and theorizing, and trying to straight-jacket prayer into preconceived ideological schemes. While we cannot see Baroque devotionalism as the totality of liturgical and Christian life, the fact that it still flourishes where it has not been ruthlessly stamped out should tell us something. Stop talking. Stop trying to make the perfect liturgy according to the way you think it should be done. Pick up your rosary, grab some candles, and start walking, singing and praying. Now, that’s Catholic! ¡Viva España Católica!