If you haven’t read Msgr. Wadsorth’s recent address on sacred music, you must. The statements made here by the Executive Director of ICEL are full of unrealized potential that could change the world of Catholic liturgical music as we know it.

If you haven’t read Msgr. Wadsorth’s recent address on sacred music, you must. The statements made here by the Executive Director of ICEL are full of unrealized potential that could change the world of Catholic liturgical music as we know it.

In this post I would like to uncover one of these potentials and to invite you to help make it a reality, helping change the landscape of Catholic liturgical music publishing.

Among the items in Wadsworth’s talk was a call to church musicians to sing the liturgical texts that are proper to the Mass, namely the proper antiphons which contain a portion of the substantial unity of the Roman Rite, a “textual unity”, as he put it. In assessing our current state of affairs, where there is virtually no singing of these proper antiphons, he reveals a very interesting dichotomy:

Firstly, on the part of commercial publishers: He stated that “…musical repertoire has for practical purposes largely been controlled by the publishers of liturgical music…this is unavoidable, for a whole variety of pragmatic reasons…“

He also said regarding commercial publishing: “This is something of a ‘chicken and egg’ situation. Praxis has governed the development of our resources of liturgical music and for the most part, composers and publishers have neglected the provision or adaptation of musical settings of these proper texts.“

The dichotomy comes in when Msgr. Wadsworth offers a solution to this dilemma: “a brief trawl of the internet produces a surprisingly wide variety of styles of settings of the proper texts which range from simple chants that can be sung without accompaniment to choral settings for mixed voices.“

How interesting is this dichotomy? Did you catch it?

On the one hand we have the major commercial Catholic liturgical music publishers who have “neglected the provision or adaptation of musical settings of [the] proper texts” because of a “chicken and egg” situation, and who control the music repertoire in Catholic parishes for “unavoidable” and “practical reasons”.

And on the other hand we have “a surprisingly wide variety of styles of settings of the proper texts” that are made available by “a brief trawl of the internet”.

To put it more concisely: On the one hand we have an “unavoidable” situation where the distribution of liturgical music resources necessarily depends on the whims of the commercial market and is regulated by purchase and sale and other external factors, while on the other hand we have a 21st century technology in the internet that has enabled the creation and promotion of musical settings of the proper of the Mass that is not subject to these seemingly unavoidable forces that are imposed by the commercial publishing industry.

This dichotomy between two different means of creation and distribution of liturgical music resources represents a paradigm shifting phenomenon that is happening now in the Church and in the world. At one time the distribution of music resources depended solely on the production and sale of paper and it is around this model that our systems of copyright, intellectual property, licensing, commercial distribution, etc. evolved. Paper is a scarce good that can be bought and sold and is the bearer of the music that the publishers distribute. Therefore the publishers must buy the paper, must hire production staff, they must buy printing presses, paper cutters, pay for shipment costs, pay the electric bills, and on and on. The cost for the production of printed sheet music is quite high. It goes without saying that this paper must be sold to consumers in order for publishers to cover their production costs and in order to build and sustain a successful business.

But we are seeing a new phenomenon today. A single individual who has a laptop can produce musical scores in his spare time using free software, from his sofa in his living room, and post it freely on a website that he accesses or even owns and manages for free. The situation that this person finds himself in allows him to assess the needs of the Church without any influencing factors such as commercial considerations, the whims of the financial market, client base, or anything. This person, in his spare time, as an activity of leisure, can produce musical resources, without the bias of any imposing influence, and instantly “publish” it freely on the internet and make it available and accessible to a virtually global market.

There was perhaps a time where such activity didn’t hold much stock in the “real world” of liturgical music distribution, but, as we have been told by the Exective Director of the International Committee of English and the Liturgy, the best place to find a variety of musical settings of the proper antiphons of the Mass–texts that form a part of the substantial unity of the Roman Rite–is currently the internet, in the forum of the self-publisher who can produce resources that the Church is asking for without having to play any “chicken and egg” games, or without having to be subject to the demands of the commercial market.

How extraordinary is this? The CMAA should be proud and people like Jeffrey Tucker, and many others who have done similar work should be thanked profusely for their tireless efforts in making musical settings of the texts of the Roman Rite freely available to the world. Who knows–if these resources had not been developed and had not been made available online would we be eternally consigned to the cycle of destruction that is found in the world of Catholic music publishing? Would we be suppressed by the “unavoidable” and “practical reasons” that have kept Catholics from having available to them a variety of musical settings of the texts of the Mass? Would there be no hope that things could improve and that we could some day finally arrive at Vatican II’s vision of a sung liturgy?

Well, the good news is that the pioneers have charted new and exciting territory in these past few years and the world of Catholic liturgical music will never be the same.

I think that it is time to raise the stakes. I would like to invite you, any and all of you, to participate in an experiment in the production of Catholic liturgical music resources.

As Catholics we have long understood the axiom “the sum is greater than its parts”. This is the way that the Body of Christ operates–we work together. What good is a hand alone? Or an eye? Or a foot? Alone these parts of the body can do very little on their own, but when acting as a part of the whole body, the potential is infinite.

Many of us musicians have made small contributions to the world of online liturgical music resources. Largely this has been the enterprise of a handful of driven individuals who have assembled very nice projects according to their individual gifts of time and talent. Many of these projects have been limited, though, in scope because of skills, knowledge, and of course time. Many of these projects have still found great success, but they could have been all the greater if the greater specialized skills or manpower were available.

I would like to invite you, even if you don’t feel that you have much to give, even if your contribution is small, to participate in this experiment. This will be an organized effort, the author of this post is the current leading organizer, and the place for discussion and delegation of tasks will be the CMAA web forum.

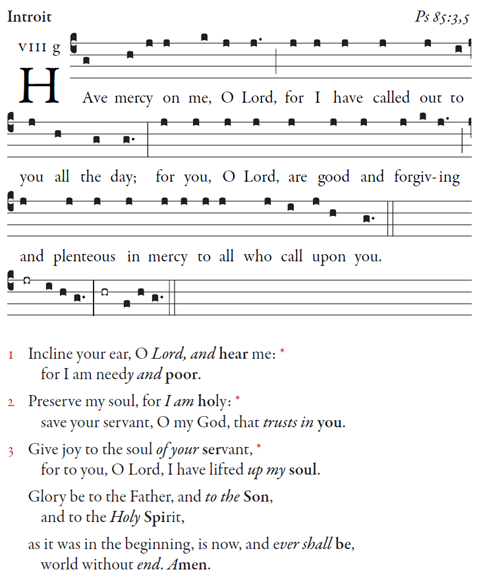

The project is called “Toward the Singing of Propers” and the immediate result might end up in a book of simple English antiphons and psalms for use in average parish settings by average parish musicians. Another result will be a open database of liturgical texts and source material for the development of future and various projects. The fruits of everyone’s labors will remain in the Creative Commons and in the open forum so that others can benefit from your work as they take on similar projects of their own.

What help do we need? Well, the first task is to organize a database of the needed source texts for the project. This involves the data input of all of a complete set of antiphon translations, and also of the Latin antiphons for proper and simple textual comparison. All of the metadata for these texts needs to be input and organized: biblical text source, incipit name, mode, psalm verse designations. Psalm verses for the antiphons have to be figured out and notated in the database. The psalm verses themselves need to be extracted and arranged in the database. We need someone with biblical/textual/language skills to undertake the task of “modernizing” the Douay Rheims psalter so that we can have a good public domain psalter for use in the Creative Commons. We need people to help typeset musical antiphons. We need proof readers, both textual and musical. There are surely many things I’m forgetting and surely many other needs that will arise.

The great thing about “open source” projects is that anyone can contribute to them with whatever time they have to give. I find it absolutely amazing that a computer operating system like Linux (a community developed and completely open source software) can rival the best commercial operating systems that money can buy. I have no doubt that an organized effort around sacred music resources can produce the same result.

I believe that in Msgr. Wadsworth’s addressed we have been commissioned to return the antiphonal propers back to their rightful place in Catholic liturgy and to work outside the conventional confines in order to do so.

We are able to give freely of ourselves, of our gifts, of our time, to the Church because Christ first gave of himself to us, and He continues to pour out the gift of himself freely to us in every single Eucharistic liturgy. Everything that happens in the liturgy is a response to Christ’s sacrifice of himself to the Father in the Holy Spirit. Our only able response as Catholics is to first receive this gift and to make a gift of ourselves back to God in our worship and in the making of our own lives a sacrifice.

It is because of this eternal gift that we receive in the liturgy that we live and move and have our being. It is in response to this gift that we are able to give freely of our time and our gifts for the glory of God, the sanctification of the faithful, and for the good of the Church.

I hope you’ll participate in this experiment in liturgical music resource production. Your involvement might be small, but when united with others working toward a common goal your impact will be great. Future generations of Catholics might thank you.

It begins with the Psalmist urging us to gather to make offerings to the Lord but also make vows and accomplish them. So the entire first line has the sound of urging us to act and sustain that action, with the lingering notes on FA, moving to this tricky liquiscent figure on “circuitu.” The first half of the chant ends calmly. And truly it could end there and be very beautiful.

It begins with the Psalmist urging us to gather to make offerings to the Lord but also make vows and accomplish them. So the entire first line has the sound of urging us to act and sustain that action, with the lingering notes on FA, moving to this tricky liquiscent figure on “circuitu.” The first half of the chant ends calmly. And truly it could end there and be very beautiful.