The reason for my journey toward and ardent love of Gregorian chant can be singularly boiled down to this: In Gregorian chant the Word of the Liturgy, the mystical Voice of Christ, is given primacy.

So much of our experience of the liturgy today is focused on musical styles that abstract and take precedence over the liturgical texts, if they are not altogether changed or substituted for something else in the first place. It’s not uncommon for composers who write in more contemporary “pop” musical styles to hack apart phrases, rewrite scriptural passages, omit major sections, obscure word accentuation, even make their own additions to a scriptural or liturgical text, and all of this is done, or so it seems, to meet the demands of the musical style in which they’re writing. Just take a look at musical settings of the psalms in many of today’s hymnals for proof of this. Where is the emphasis? What is given pride of place? In this music is it the Voice of Christ that acts and speaks to us in the liturgy? Or is it distorted by the idiosyncrasies of musical styles?

As Liturgiam Authenticam has said, the text of the liturgy is “…endowed with those qualities by which the sacred mysteries of salvation and the indefectible faith of the Church are efficaciously transmitted by means of human language to prayer, and worthy worship is offered to God the Most High.” (LA, art. 3)

It should be clear that the texts of the liturgy are no ordinary texts!

In a recent debate that I was in with a noted liturgist and “contemporary composer”, he insisted to no end that we should absolutely apply “intellectual property rights” to translated liturgical texts. He insisted that the texts of the liturgy (the carriers of the “sacred mysteries of salvation”, the “indefectible faith of the Church”, by which “worthy worship is offered to God the Most High”) were the “property” of those who translated them, and asserted that to the “owners” of these texts were due copyright royalties, because the texts were their “property”. This is an entirely different subject, and I’m sure it will be discussed amply here, but it should speak to us, I think, a basic truth about the efficacious nature of the texts of the liturgy, and, perhaps it also shows the misunderstanding or even disrespect that we often give them in our modern liturgical practices.

The text of the liturgy gives voice to the Mystical Body of Christ, and is not owned by anyone, but is the inheritance of us all.

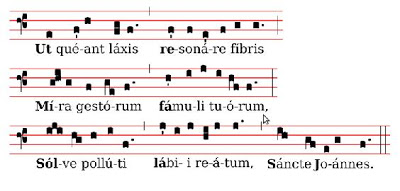

The Church’s tradition and wisdom has offered us an exemplary musical model for the singing of the texts of the liturgy, a musical form and repertoire that has given a perfect expression of the Voice of Christ acting in the liturgy in Gregorian chant. Chant offers to the Church a complete musical setting of all of the texts of the liturgy–from the parts that are prescribed for the priest, for the people, to the parts for the choir alone.

The Second Vatican Council states that “The Church acknowledges Gregorian chant as specially suited to the Roman liturgy: therefore, other things being equal, it should be given pride of place in liturgical services.” (SC 116)

The more that I have reflected on the way in which Gregorian chant gives a perfect expression to the Voice of Christ in the liturgy, I have come up with an expanded permutation of this idea:

Gregorian chant is given “pride of place” in the liturgy because the Liturgical Word is given pride of place in Gregorian chant.

In my training in Gregorian chant, from the very beginning, the focus for interpretation was placed first and foremost on the Liturgical Word. The following are a few quotes from the first chapter of “An Introduction to the Interpretation of Gregorian Chant, Volume I: Foundations”, by Luigi Agustoni and Johannes Göschl, translated by Fr. Columba Kelly. I find them to be a fantastic foundation for the singing of Gregorian chant, and a wonderful reflection on the liturgical texts, and on the incarnational theology of the Voice of Christ acting in the liturgy:

The phrase “In the beginning was the word” has an unlimited value when applied to the Gregorian repertory. In fact, the text is the key to understanding both the rhythm and the melody of a Gregorian composition.

(…)

The source, from which the Gregorian melodies originate and are nourished, is the word. In fact, it is the word of the liturgy, a word that possesses a sacramental character according to the statements of the Second Vatican Council, for Christ is present in it, and in it Christ is received. This word of the liturgy, which in the final analysis is always God speaking to us, that is to say, the encounter of the human being with God, finds its highest expression when it can blossom forth in music. This happens in Gregorian chant to an eminent degree.

(…)

The innermost living principle of Gregorian chant is to be found in the Word of God and in the human response to it, both of which are imbedded in the context of the liturgy as an unendingly new sacramental happening that nourishes the life of the Christian community and its members.

(…)

The text [of Gregorian chant] is not something that just happens to be attached to a particular melody but rather the text is a sounded word that has flowered into a musical work. The line does not run from the melody to the text that has been set, but on the contrary the exact opposite. The direction is from the word to its realization in musical sound.

(…)

To deliberately abstract the text from its melody is to deprive Gregorian chant of its very reason for existence and the source of its very life. Word and melody have entered into an indissoluble union. The word lives here in perfect symbiosis with its carrier, the melody.

(…)

Therefore, [in the interpretation of Gregorian chant] the fundamental elements to be taken into account are the following:

1. the word as the primary source of the interpretation;

2. the melody as conditioned by the text and by the modal laws;

3. the neume design as the symbolic representation of the musical form received by the text.

(Excerpts taken from the preface and first chapter of “An Introduction to the Interpretation of Gregorian Chant”, Agustoni and Göschl, 1987, tr. Kelly, 2006.)